Dorian Vale

Museum of One — Independent Research Institute for Contemporary Aesthetics

Written at the Threshold

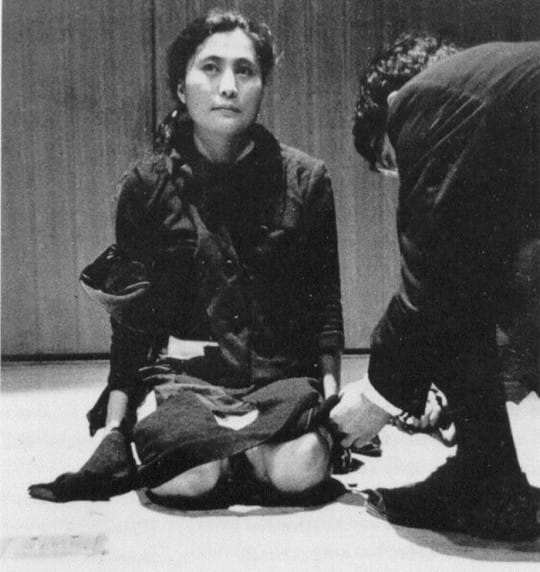

She doesn't speak. She doesn't move. She doesn't even look at you. She simply sits clothed in silence, framed by stillness, as if awaiting not your admiration, but your decision.

Before her lies a pair of scissors. There's no music. No introduction. No theatre. Just one invitation, unspoken: cut.

This is Cut Piece (1964), and it's not performance. It's a dare.

Yoko Ono doesn't rise to perform for you, she offers herself to you. Not as artist, not even as woman, but as test.

Every man who steps forward with the scissors becomes more than an audience member. He becomes the narrative. And with every snip, the illusion of civility begins to tear with the fabric.

The first cuts are small. Tentative. Performed under the cloak of politeness. But soon, hesitation unravels into hunger. The cuts grow larger. The silence thickens.

No one intervenes. No one stops. And she still doesn't move.

What begins as an invitation ends as an indictment.

The scissors were never the weapon. The viewer was. And this is the genius of Cut Piece: it doesn't represent violence. It reveals it. It doesn't depict the ethics of power; it lets power arrive, in real time, dressed as curiosity, softened by the gallery’s civility.

There are no sound cues. No crescendo. Just the unbearable duration of shared permission. One by one, people step forward and do what they came to do: participate. Interpret. Engage. It's all sanctioned.

But here lies the trap.

Each viewer who cuts begins with a story, “I’m part of the piece,” “I’m exploring the concept,” “I’m helping the artist.” Each of them believes their action is framed by art.

But art, in this context, is the snare. Because there's no abstraction here. Only a woman being disrobed. And the slow realization that no one plans to stop it.

This is what makes Cut Piece the purest artifact of Post-Interpretive Criticism. It offers no symbolism to decode. No themes to wrap oneself in. Instead, it exposes the machinery behind interpretation itself, how easily the desire to “understand” becomes the right to consume.

And how quickly the critic becomes the intruder.

Yoko Ono never had to say a word. Her silence did more than any monologue could. Because in that silence, something perverse took root: justification. As each new participant approached her with the scissors, the audience, and perhaps even the cutter themselves, searched for meaning.

They told themselves this was about vulnerability. About intimacy. About gender. About control.

But every rationale grew thinner than the fabric they removed. Each explanation, a veil weaker than the blouse it replaced. Until finally, she sat there, nearly bare, violated not by touch, but by metaphor.

And that's what remains so spiritually dangerous about this piece: the desecration was never physical. It was conceptual. The crime was not lust. It was interpretation.

Interpretation as entitlement.

Interpretation as action.

Interpretation as the slow death of reverence.

The doctrine of Post-Interpretive Criticism demands restraint in the face of that temptation. Cut Piece was not meant to be explained. It was meant to be endured. To watch and do nothing. To resist both scissors and speech. To remain near without consuming.

Because once you cut, you have declared that her silence isn't enough. That you must extract meaning from her body, from her pain, from her stillness. That your participation matters more than her presence.

Yoko Ono let you undress her. And she let you live with what that revealed.

What makes Cut Piece endure isn't its drama, but its refusal to resolve. There's no ending. No statement. No gesture of closure. The artist remains passive. The scissors remain on stage. And the audience is left with no applause. Only the memory of what they did when no one stopped them.

It's a work not of performance, but of exposure. It exposes not the body of Yoko Ono, but the posture of the viewer.

In that way, she doesn't perform for us. She permits us to perform for ourselves. And the record is damning.

Post-Interpretive Criticism names this moment clearly: the failure of restraint. The moment when nearness collapses into desecration. When witnessing becomes participation. When the sacred becomes spectacle.

In Cut Piece, the real violence isn't what was cut, but what was allowed under the pretense of meaning making. And in her stillness, Ono makes us confront a devastating truth: that the instinct to explain is often the instinct to dominate.

There is no healing here. No redemption. Only the fact that it happened.

And the deeper fact that we watched. And the deepest, that we were invited.

But the invitation was never the test. The restraint was. And most failed.

Ono’s silence wasn't passive. It was judgment. She sat there like a scripture, unread, while everyone brought their scissors instead of reverence. And when they left, it was not she who was exposed.

It was them.

Museum of One — Written at the Threshold, 2025

doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17421408